Rocky Mountain American Society for Biomechanics - 2019

Published in Estes Park, CO, 2019

Intro

An open question in motor control is how the brain selects the duration of a movement. We recently proposed a theory capable of explaining both the actions one prefers to take, as well as the speed of the movement that follows [1]. Each movement is assigned a utility consisting of the reward to be acquired minus the effort cost to acquire it, both discounted by time. Critically, the effort cost required to make the movement is represented objectively by its metabolic cost. Previous modeling efforts have assumed that effort costs in reaching scale quadratically with mass [2]. In contrast, empirical measurement of metabolic cost (i.e. objective effort cost) in locomotion suggests a linear scaling [3]. For reaching, the effect of mass on metabolics has not been measured. Here, we quantified metabolic cost of reaching as a function of mass, and then measured how preferred reach speed varied with mass. We asked if changes in speed were consistent with the theoretical predictions of a movement utility where effort of reaching depended on its metabolic cost.

Methods

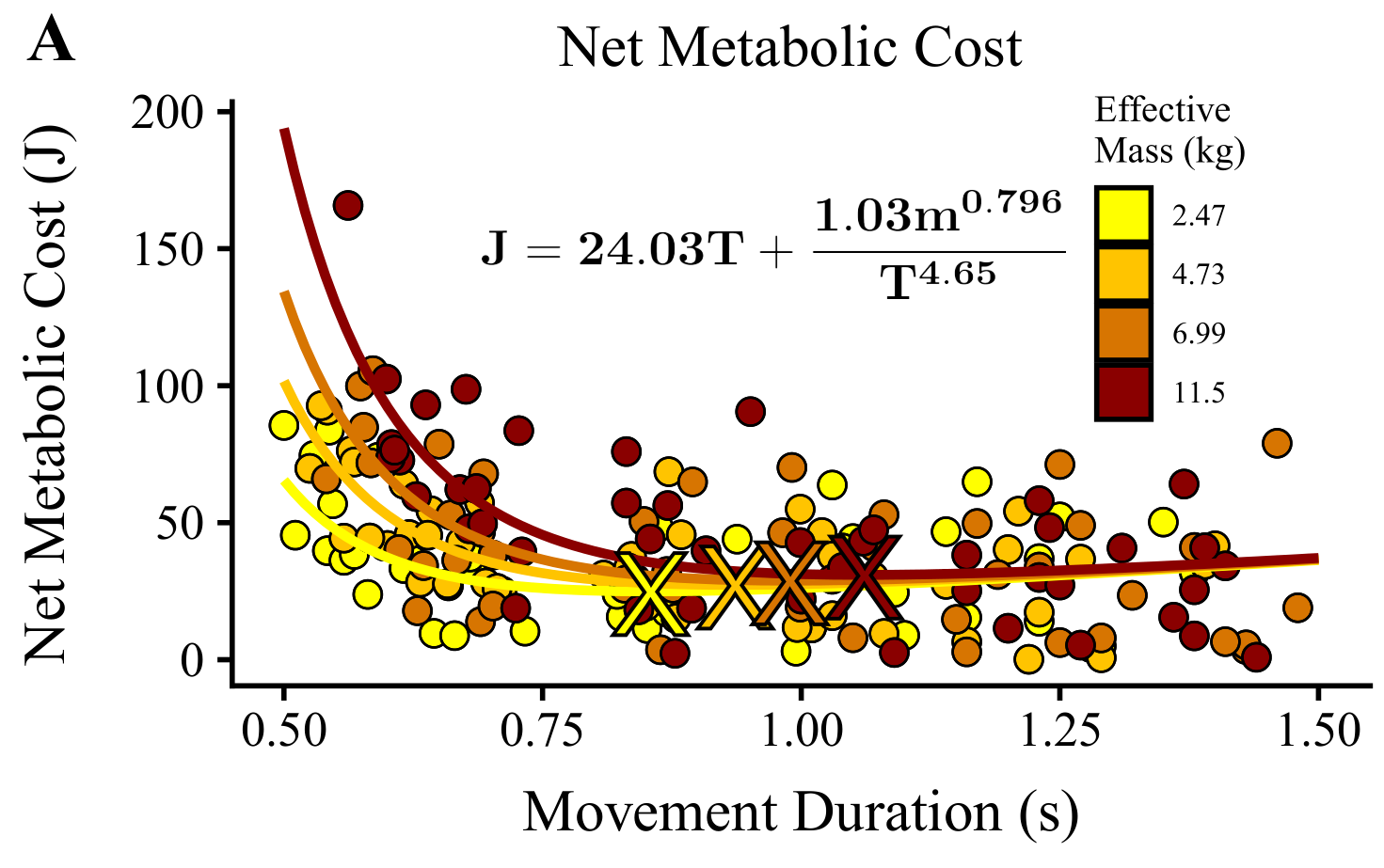

Experiment 1: Metabolic cost of reaching with added mass. We measured the metabolic cost of reaching via expired gas analysis. Eight subjects made horizontal reaching movements while holding the handle of a robotic arm. We computed net metabolic power in four mass conditions: effective mass of robot+human arm of 2.5, 4.7, 7.0, and 11.5 kg. For each condition, subjects performed 5 minutes of reaching at six different movement durations, ranging from 0.4s to 1.3s. A single reach required moving 10cm from a starting circle to a target at the specified duration. Targets were oriented at 45o, 135o, 225o, and 315o in a pseudorandom order. We fit subject data to determine the relationship between metabolic power (dot(e)), effective mass of the arm (m), and movement duration (T) according to the equation: dot(e) = a + (b*m^2)/(T^d) Eq. (1). By integrating this equation over time we are able to calculate metabolic cost.

Experiment 2: Preferred reaching duration with added mass. Twelve additional subjects performed reaches with a similar target set-up but without duration requirements. Subjects were instructed to move at a comfortable speed, and they completed 200 trials in four mass conditions (2.5, 3.8, 4.7, and 6.1kg) in a randomized order. The effect of added mass on preferred movement speed was assessed using a linear mixed effects model.

Experiment 3: Mass effect across target sizes. To control for the effect of target shape we conducted two more tests with varying target shapes in similar positions to Exp 1 and 2. Twelve subjects made reaching movements to an arc shaped target smaller than in Exp 2. Another 18 subjects made reaching movements to a target much larger than in Exp 2. In both, subjects were free to choose their duration.

Results

Experiment 1: The metabolic cost curves for each mass condition are given in Panel 3, with a=24.03 (p«0.01), b=1.03 (p=0.03), c=0.796 (p«0.01), d=5.65(p«0.01). As expected, increasing mass increased the metabolic cost of reaching. Importantly, increased mass had a sub-linear effect on the metabolic cost of reaching.

Experiment 2: Added mass increased movement duration (p<2e-16), decreased peak velocity (p<2e-16), and did not affect maximum excursion (p=0.09) shown in Panel 4.

Experiment 3: The effect of mass was conserved across the different target sizes, where mass increases movement duration (p<2e-16, Panel 6).

Model Predictions: We write the utility of that movement as: J = (α-aT-(bm^c)/(T^d))/(1+γ*T) Eq. (2), where α is reward, and γ is the temporal discount factor. The results are shown in Panel 5 in both absolute and normalized units (the only free parameter is α, γ was set to 1). Mass1,2 both over predict the movement duration, and neither net nor gross metabolic cost predict the movement duration. The utility model is able to predict the movement duration well. However, the utility model and both metabolic cost measures are able to predict mass based changes in duration across experiments (Panel 6).

Conclusions

In many models of motor control, effort scales quadratically with mass. Here, we measured metabolics of reaching and found that it increased sub-linearly with mass. We also find that adding mass increases movement duration in a similar manner across target shapes. Using a model of movement utility where effort was represented objectively as metabolic cost, we found that the speed with which people chose to reach increased at a rate that was consistent with a sub-linear increase in effort as a function of mass.

References

- Shadmehr, (2016) A representation of effort in decision-making and motor control. Curr. Bio.

- Torodorv, (2002) Optimal feedback control as a theory of motor coordination. Nat. Neurosci.

- Bastien, (2005) Effect of load and speed on the energetic cost of human walking. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol.